In the middle of a dirt yard, two lions – probably no more than a few weeks old – are crammed into a cage the size of a bar fridge. Their fur is scrappy; they yowl through the bars for their mothers. An older lion tries to walk by, but its back legs collapse behind it, a product of inbreeding. Groups of adult lions restlessly prowl the fence-line of their tiny, dirty enclosures. These are the heart-breaking opening scenes of Blood Lions, a new documentary that exposes the realities of the multi-million dollar lion breeding industry in Africa. Here’s the trailer:

There are currently thousands of lions and other predators being held in captivity across the continent, bred for use in cub petting, lion walking and volunteer recruitment, as well as canned hunts – trophy hunts in which the animal is detained in a confined space, giving the hunter an easy advantage. In South Africa alone, around 800 lions are shot in canned hunts each year. While many of the people operating the country’s 200 or so captive breeding facilities do so under a guise of conservation and research, it’s a far cry – a mighty roar – from the truth. The truth is that predator breeding and the industries that exploit lions for entertainment in Africa need to be stopped.

That’s why today, on World Lion Day, Intrepid are proud to announce we’ve signed Blood Lions’ ‘Born to Live Wild’ pledge. Sadly, tourism is a huge contributor to animal cruelty around the world. The thing is, most travellers who participate in activities like cub petting or walking with lions absolutely love animals. They just have no idea what goes on behind the scenes.

We’re passionate about animal welfare and work hard to ensure our trips in no way contribute to the harm or exploitation of animals, both domestic and wild. It’s the reason we ended elephant rides on our tours in 2014. While we’ve never, ever had hunting on any of our trips, for us, the ‘Born to Live Wild’ pledge is a promise to you to never knowingly work with operators offering lion walks, cub petting or other interactive wildlife activities that contribute to the cycle of breeding and exploitation of lions in Africa. It’s also a promise to raise awareness of these industries amongst our travellers and the broader community.

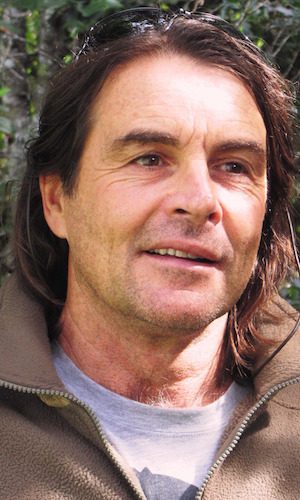

To help with that last part, we sat down with environmental journalist, safari operator and expert consultant at the heart of Blood Lions, Ian Michler.

What’s your story? How did you become so passionate about fighting the abuse of lions raised in captivity?

During the 1990’s I lived and worked in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. While researching the sustainability of trophy hunting for lions in this region, I followed some leads that took me straight to the breeding and hunting farms in the Free State, South Africa. That was the beginning of my work on predator breeding and canned hunting.

Why did you, Producer Pippa Hankinson and the rest of the team decide to make Blood Lions?

I had for some time wanted to document what was going on and had spoken to Nick Chevallier, the film’s cameraman and Co-Director about this, but we never found the right partners. And then Pippa Hankinson came along with her idea to make a film – and she was motivated to do so after visiting one of South Africa’s predator facilities. The three of us then set about our way and this was the beginning of Blood Lions the film and the global campaign.

What is lion walking, and how is it harmful?

The ‘walking with lions’ operations are another revenue stream in the chain of exploitation. Cubs start being petted and handled from about a week old, but by the age of 4 to 5 months, they become boisterous and can bite handlers. This is when they move them to walking operations and they stay here until they are about 18 months. There have been numerous incidents of tourists being bitten or attacked by predators during these stages.

What about cub petting and ‘orphan’ cub voluntourism?

This is quite possibly the most lucrative part of the entire revenue chain. Young students, or those involved in taking a ‘gap year’ are lured to these farms or facilities by being offered the chance to pet, cuddle, sleep and play with lion cubs all day long. And they are also sold the fraudulent line that by becoming involved they are making a contribution to conservation and securing the future of the species when in fact the visitor is simply part of a chain of exploitation that typically ends with the animals being shot or culled for the lion bone trade. And those that do volunteer pay significant sums of money – on some of these facilities, they were making in excess of US$100 000.00 a month.

Many captive breeding facilities, volunteer centres and lion walk providers mask their businesses as research facilities or ‘conservation’ sanctuaries. How can travellers tell the difference between legitimate operations and exploitative ones?

It is accepted around the world that true sanctuaries do not breed, trade or interact with wildlife. The crux here is that people thinking about visiting or volunteering need to do their research properly and ask the right questions. Do not accept answers or explanations as fact. And we are hoping that in time, organizations such as Fair Trade Tourism will be in a position to come up with a grading system for each facility. But the bottom line is that the best way to deal with these issues is to stop all the breeding – we have no reason to be breeding all these predators.

What do you think propels tourists to want to cuddle lion cubs, take selfies with tigers and generally disrupt the ‘wildness’ of wild animals?

This is partly to do with the thrill of holding or coming so close to such a revered wild creature, and then also for selfish reasons involving identity, ego and control, especially when it comes to shooting lions.

In many instances these desires are further exploited by the owners when they lure visitors who want to make a contribution to conservation or animal welfare – it’s a cruel triple con: the visitor or volunteer is being exploited, the individual lions and the species is being exploited and in most cases, the conservation and marketing message is wrong or even fraudulent.

How can we change this mindset? After seeing animals in the wild, many travellers say they return from an African safari ‘changed’. Is travel one solution?

The cub petting and canned hunting operations are like the fast food outlets – they offer instant and easy gratification. So it is a combination of education and awareness and yes; promoting travel to national parks and reserves to see how lions and other species should live.

Do safaris affect the wildness of African animals in any way? How can we ensure our safaris are as responsible as possible?

Use the ground operators and lodges/camps that have the best records, which will include having the best guides. These people will mostly be ethical and responsible and the visitors should get the best and most reliable information on ecology and conservation. They are highly unlikely to be fed the rubbish and lies that one so often hears from so-called guides on the predator facilities.

Tell us about the ‘Born to Live Wild’ pledge. How will it contribute to the fight against predator breeding, lion walking, canned hunting and other exploitative industries?

First prize in our campaign to have predator breeding and the exploitation stopped would be to engage constructively with government and other decision-makers.

But failing that, the next option is to focus on all those that continue to support these industries, and the tourism industry has been a significant supporter, often inadvertently, by taking guests to the lion facilities. The ‘Born to Live Wild’ pledge is about making the wider tourism industry aware of what is actually going on. And if we are to live up to the marketing claims we make about ethical and responsible tourism, and our commitments to support legitimate conservation, then most of these lion and predator facilities do not qualify for support.

According to the documentary, canned hunting has been happening since 1977. Why has it taken so long for the world to know about it and take action?

For a number of reasons: 1) the entire industry is a murky one and those involved are not forthcoming with what they do, how they do it and why they do it as they understand that to the vast majority, these practices are completely unacceptable. So it has taken time to unravel their secrets, 2) sectors such as the wider trophy hunting industry that could have been affective in closing these operators down have mostly kept quiet or had a large number of their membership involved, and 3) government and other decision-making bodies that should have acted have either turned a blind eye, or given their tacit support.

The breeding of lions in captivity for use in canned hunts, lion walks, the lion bone trade and cub petting is on the rise. In the documentary, we’re told we’re “sitting on a ticking time bomb”. Why is it important that we do something now? Are South Africa’s lion populations in danger?

The quote from the film was used to refer to the growth in the numbers of predators in captivity and in most cases, the awful conditions they survive in.

While South Africa’s wild lion populations are arguably regarded as stable (not everyone agrees with this assessment), those across the rest of the continent are in trouble. But the crux here is that lions being bred in captivity have little to no conservation value. The real challenges around lion conservation involve securing habitat and reducing the intense human/animal conflict situation that often results in lions being killed by humans.

At the end of the day, the most important factor is to stop the breeding – if we stop all the breeding, then we have a time-line on the problem and once that has passed, we will not have to worry about who may be legitimate and who is not.

Want to help? Visit the Blood Lions website or sign up to the Facebook page. And if you travel to a southern African country, don’t visit any facility that offers cub petting, walking with lions or other exploitative activity involving wild animals. We believe wild animals should be exactly that – wild. See lions in their natural habitat on an Intrepid African safari, and support the good kind of wildlife tourism.

Feature image c/o Blood Lions.