“Please don’t walk around after dark,” Mohan, the village chief, tells us as he shows us around the small Nepalese community in the late afternoon sun. He doesn’t speak a lick of English, so Srishti, our leader, translates. “We had an elephant come through last night. It didn’t do any damage, but the dogs all went crazy.”

Our small group of nine has just arrived in Shivadwar Village, a community in Madi Valley found inside the southern buffer zone of Chitwan National Park in Nepal. It’s been a long journey – about six hours by bus along bumpy roads through tiny villages, and it feels like we’re a world away from the busy streets of Kathmandu.

This is about as rural as it gets – a few dusty trucks stand in ramshackle sheds, kids roll past on old bikes, curiously eyeballing our group. Dogs sniff around our legs while chickens peck in the dirt. There’s one road in the village, and it appears its main source of traffic comes from farmers ambling along behind their herds of goats, and children heading home from school.

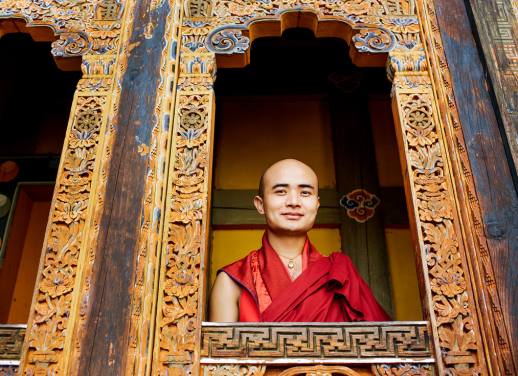

Mohan, village chief.

Land here is among the most fertile in Nepal, and the farmers take pride in their crops of rice, beans, corn, potatoes and flowers. As we walk around the village, each allotment sings with colour. Mohan boasts his farm is the best, his crops the most bountiful. I feel like, as village chief, Mohan is taking a bit of creative license. All the food we eat during our stay has been grown right here (and it’s so good!).

INTERESTED IN A VISIT TO MADI VALLEY? EXPLORE OUR RANGE OF ADVENTURES HERE.

While the crops are well established, tourism here is relatively new. Despite its close proximity to Chitwan, one of the best national parks in Asia for wildlife spotting, many villages here don’t see any direct benefit from tourism. Up until a few years ago, some of the locals were operating simple homestays, but the quality of the properties was poor. They hosted Nepalese visitors, but had no way of promoting themselves to foreigners. Madi Valley wasn’t on the grid, so there was no electricity, and the area was renowned for its issues with human-wildlife conflict. Elephants, deer and wild boar from the national park were frequent intruders, feeding on crops and trundling through fields, which led to a shortage of food and damage to property.

Exploring the village at sunset.

In 2015, the community began working with Nepal’s World Wildlife Fund (WWF-Nepal) to try to find a solution to Madi’s noisy (and destructive) neighbours. WWF-Nepal applied for funding through Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trading (DFAT), and that’s when Intrepid got involved: to help establish the village as a community-based tourism (CBT) project that would create jobs, generate income for families, and empower the locals, particularly women, economically, socially and personally.

This experience gives travellers, like us, the opportunity to really immerse themselves in a completely different way of life. It’s a responsible way to travel too; CBTs are all community owned and managed, meaning cash comes into the community and it stays there.

RELATED: HOW WE’RE DEVELOPING COMMUNITY-BASED TOURISM IN MYANMAR

Arriving in Madi Valley.

One direct benefit of tourism can be seen right in front of our eyes – a new fence that rings the community. It was paid for using tourism dollars and now protects the village and crops from unwanted wildlife intrusions. Some wildlife still make their way in occasionally, like last night’s visitor, but it’s far less common now.

As the sun sets, Mohan leads us to the community dining room for dinner. Like most places in Nepal, dal bhat is on the menu. There are lots of extra trimmings, like fried potatoes, garlicky greens, two types of vegetable curry, bread, and an amazing spicy coconut chutney (along with the usual steamed rice and lentil soup, which were delicious).

RELATED: THE CHANGING FACE OF TOURISM IN RURAL VIETNAM

The women in Madi Valley were always smiling.

Dal bhat – yum.

Two women dish up seconds for us; one is FaceTiming her sister in a neighbouring village, and turns her phone around to ‘introduce’ us. Neither woman speaks English, and none of us speak Nepalese, so we all smile and wave at the screen.

After dinner, we head outside, where the sky is smoky and the colour of a bruise. The women bring out boxes of clothes and jewellery, and take turns dressing us in traditional Nepalese garb. One woman holds a velvet shirt up to me, then shakes her head. “Too big!” she exclaims, at my ‘large’ build. She scrambles through the box, gives up on finding something that will fit, and instead wraps me in a checked swathe of fabric. Another girl clips a string of pearls around my neck and gives me a pair of earrings to wear.

Srishti gets involved in dressups.

Our village hosts.

The others in my group are similarly adorned. Men are helped into bhangras – a fabric sling that’s worn across the shoulders, like a backpack – and given woollen topis to wear on their heads, while the women are pinned into saris, red bindis stuck to their foreheads.

We pose for photos, then head back into the community centre for a cultural performance. Mohan gives us a history of the area; of how the gods descended and created the valley between the mountains. Along with the women who cooked our dinner and dressed us, people from neighbouring villages crowd around the door to watch. They laugh in parts of Mohan’s speech, and look solemn in others.

CHECK OUT OUR FULL RANGE OF SMALL GROUP ADVENTURES IN NEPAL NOW

The first performance of the night tells of how this community – the Pun Magar people – came to the valley. A guttural drone emanates from a group of singers in the corner. They harmonise with each other, the sound reverberates into my bones. A band of men stand in front of them, each with a different musical instrument, and they play along – tapping a drum, plucking a string – as they step in a slow, considered circle. I don’t have a clue what’s going on, but the sound and movement is mesmerising.

The cultural performance made us feel like we were part of something.

We’re treated to a few more dances after this. In one, three men glide around the room. Their faces are painted in lipstick and rouge, and they flick their hands delicately towards the ceiling. In another, two women dance with copper plates resting on their palms. They invite a few of our group up to join them, with clattering results.

I’ve been to cultural performances like this before, and have never really enjoyed them much. They often feel inauthentic, but there’s something special about this one. Everyone’s smiling, and laughing, and we’re all having a good time. It feels like, despite the language barriers and very different ways of life, we’re being welcomed into the community.

Even though we were in Madi Valley as part of a small group adventure, it didn’t feel like a tourist experience. We were the only group there, making it feel like we were guests in someone’s home. Everyone in the village was happy to see us, and made us feel welcome and looked after. It’s a benefit of travelling with Intrepid – they facilitate those genuine off-the-beaten track experiences.

As we walked back to our little houses after the community performance, I kept my eyes and ears open for incoming elephants. But the only sound was the laughter from the village hall, the occasional dog bark and the hum of crickets seeing us off to sleep.

Interested in visiting Madi Valley? You can on one of these small group adventures – click here for more information.

All images by Matt Cherubino.