Tasmania’s wukalina Walk is an Indigenous-owned, multi-day hike through some of the most stunning scenery on Australia’s wind-battered southern coast. For travel writer Kerry van der Jagt, it was a life-changing experience – a walk back in time, tracing the footsteps of the palawa.

This blog was brought to you in partnership with Welcome to Country, a not-for-profit marketplace for Australian Indigenous experiences.

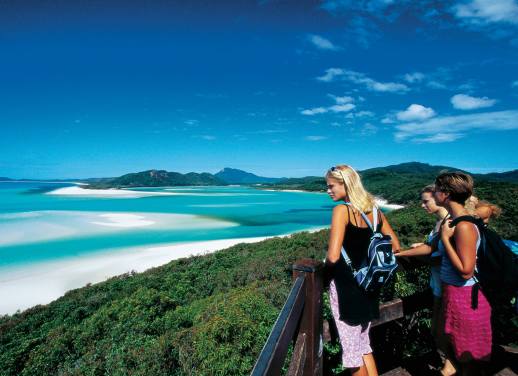

The Bay of Fires is beyond compare. An arc of wild beauty, where peacock-blue water froths against bone-white sand and sea eagles soar against an enamel sky. Hemmed by fluorescent grass trees and pinned in place by lichen-covered boulders, it is arguably one of the loveliest stretches of coast in the world (with the Lonely Planet badge to prove it).

I’m on the final leg of the four-day wukalina Walk, Tasmania’s first Indigenous–owned and –guided multi-day hike, starting from wukalina (Mount William National Park) and ending in larapuna (Bay of Fires) on the north-eastern edge of the state.

At intervals we pause, foraging for saltbush – which is used to add flavouring to kangaroo meat – or snatching a piece of sea spinach, eaten as briny salad greens. Our pace is slow as we scan the wet sand for sea treasures. One minute it’s a drift of sea sponges, the next it’s the silver thread of a seahorse. Later, we’re standing ankle-deep in cockle shells.

As we stroll along, our young guide Carleeta Thomas, a descendant of Mannalargenna, a renowned 19th-century warrior chief, shares her stories about connection to Country, and explains how the walk is allowing her people to regain their independence and reclaim their culture, birthright and palawa kani language (always written lower case).

For thousands of years this remote coastline – named the Bay of Fires in 1773 by English explorer Tobias Furneaux – was the traditional homeland of the palawa. Then, within three decades of the invasion by British colonists in 1803, the original inhabitants of lutruwita (Tasmania) were murdered, brutalised and enslaved to near annihilation. It was systematic genocide on a grand scale.

While textbooks will have you believe that the last Tasmanian Aboriginal died in 1876, when local woman Trukanini passed away, it’s a little-known fact that 47 First Nations people survived on Wybalenna (Flinders Island) after being detained there. It’s the descendants of these survivors who now lead the wukalinaWalk: a project of hope, survival and recognition, more than a decade in the making.

“The walk was founded by palawa Elder Clyde Mansell,” explains Gill Parssey, General Manager of wukalina Walk. “In conjunction with community and the Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania, the project came about as a way for palawa people to come onto their cultural homeland and share their stories through tourism.”

Day One sees us trekking up wukalina (which, at 215 metres, is more mound than mountain) before turning towards the coast to spend two nights at the wukalina Walk’s standing camp of krakani lumi (resting place). Designed by Hobart architects Taylor + Hinds, the award-winning camp consists of five elegant sleeping pods and a chic, eco-friendly communal building.

“The design of the pods is based on the domed shape of the palawa seasonal shelters,” says Gill. “The sleep that you have here feels like being in a cocoon. It’s incredible how well they knew the environment and how to situate themselves in it.”

After being welcomed by a smoking ceremony, we’re treated to a twilight barbecue of freshly caught scallops, mutton bird and doughboys cooked over an open fire pit. As the stars blaze across the night sky, Carleeta and two other palawa guides, Danny and Djuker, talk to us about Muyini the father spirit of the palawa people, and Earth Mother, the giver of all things.

“For our young guides, the opportunity to share stories with visitors gives them a new-found sense of pride and independence,” says Gill. “It also means the correct stories are now being told.”

If Day Two around camp is a gentle day of learning cultural practices, such as shell stringing and basket weaving, then the long walk of Day Three is a time for quiet contemplation. Drawn ever forward by the call of the ocean, I reflect on just how far we’ve journeyed; not the 34 kilometres we have trekked, but the thousands of years of palawa history, which is being reclaimed, one step at a time.

We spend our final night in a restored lighthouse keepers’ cottage on the Aboriginal-leased land of larapuna (Eddystone Point lighthouse precinct). Aboriginal artwork, an open fire-place and communal lounge/library invites further discussion; how much we have to learn from First Nations peoples about caring for Country, about the spiritual connections palawa people have to their land, and how we all have an obligation to acknowledge the wrongs of the past.

“Universally, our guests say the walk has been life-changing,” says Gill. “They feel transformed, their perceptions have changed and they want to learn more and do better as allies.”

Ready to trek the wukalina Walk? Welcome to Country has all the info you need over here. For more incredible tours around Australia, check out Intrepid’s First Nations cultural experiences.

The writer is a descendant of the Awabakal people of the mid-north coast of NSW.